What this means is that the visual becomes ever more fundamental to the Digital Humanities, in ways that complement, enhance, and sometimes are in tension with the textual. There is no either/or, no simple interchangeability between language and the visual, no strict subordination of the one to the other.

Burdick et al. “One: From Humanities to Digital Humanities,” in Digital_Humanities (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012), 11.

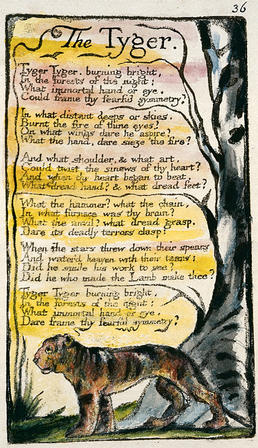

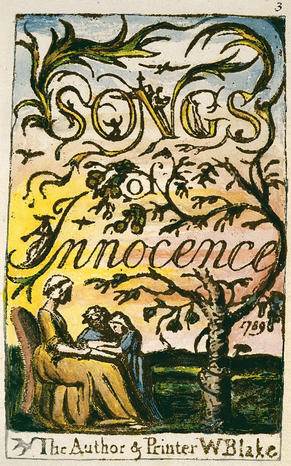

I like the way that this passage approaches the intersection between words and images. Rather than privileging one over the other, the authors recognize that the visual and the textual (which, as they point out, is also a visual system) are two different modes of expression that the Digital Humanities often seeks to integrate. Using a neologism from Theodor Nelson, the authors go on to suggest that Digital Humanists must seek to find “meaningful intertwinglings” between images and text. This passage initially caught my attention because it called to mind the work of William Blake, who I studied last spring in a class on Romantic poets. Blake’s work embodies the “intertwingling” of words and images — his poetry books were etched onto copper plates, then printed and hand-painted. The visual and the textual are not “interchangeable,” but rather inform each other. I thought that this connection to Blake was interesting because it shows that the mixing of text and images is not new to the humanities, but is more important than ever in the digital age.

Another reason that I thought of William Blake is the digital archive that contains full color copies of his works. The archive allows students to compare different versions of Blake’s books and poems (because they were painted by hand, each copy is different). Traditionally, anthologies only publish one or two of the complete paintings, and print the rest of Blake’s poems only in text. However, the archive allows students and scholars to better appreciate Blake’s work as he originally intended it to be viewed. I think that this is a very cool example of a Digital Humanities project, and I would be interested in exploring other digital archives and finding similar tools that aid analysis.

In addition to the connection to Blake, the above passage from Burdick et al. made me think about my own scholarly work and how it is presented. The passage is part of the authors’ larger emphasis on visual literacy and the importance of design in the Digital Humanities, and it grabbed my attention because in my time at Carleton, many professors have privileged the textual (writing papers) over visual ways of presenting an argument. I was inspired by the idea that scholarly work could be presented in a mixed-media mode, and it made me think of possible future projects. Image-based presentations are one obvious example, but I also could see creating an annotated copy of a work, with highlighted lines that offer critical analysis or historical background. This type of project could synthesize work from various critics and include images of the original manuscript or of important historical figures, or even “distant reading” data. One thing that I hope to gain from this class is the confidence and knowledge to create some sort of digital thesis or explanation of a text. I like the idea that the visual and the textual can be combined, not only in the work of artists like Blake, but also in presentations of scholarly research.

David, I really loved your commentary on combining the visual with the textual. Some of my favorite projects at Carleton have been posters and I’ve noticed that using a visual form of communication forces me to be much more thoughtful and precise about my language. To that point, I am looking forward to learning more about data visualization to better understand how graphs and charts can communicate complex information.

Hi David! I have also noticed that a lot of the classes I’ve been in at Carleton have emphasized textual arguments over visual ones, and I agree with what Grace said about how visual representations make me consider my words more carefully. I’ve always enjoyed making presentations more than writing papers, partly because I think for visual learners like myself, I get a lot more out of an image than from text, and it’s really cool to think about how Digital Humanities can integrate that into more traditional humanities methods.